This Holiday season, you may hear the same dish called both sweet potatoes and yams. Which is it? What are you eating?

Growing up, I remember my mom making what she called “candied yams” that came in a purple and white can. She mashed them, placed them in a casserole dish, and added a generous topping of mini marshmallows. I loved when I could sneak a few marshmallows before the dish went into the oven.

Some years later, she referred to what looked to be the same dish as “candied sweet potatoes”. She did buy sweet potatoes in the produce department instead of the purple and white can. But the recipe didn’t look any different. Were we really eating a different vegetable?

The truth is, yams and sweet potatoes are two entirely different plants.

The yam, genus Dioscorea, is native to Africa. The Sweet Potato, Ipomoea batatas, is native to tropical Central and South America, including the Caribbean.

Botanically, yams and sweet potatoes are not close relatives. Yams are more closely related to lilies than the sweet potato; sweet potatoes are more closely related to morning glories than to potatoes!

Reportedly Columbus spread the sweet potato throughout the “New World” including what is now the United States. Spanish explorers brought the sweet potato as far as Asia; the Portuguese introduced sweet potatoes to India.

Of course, Columbus and other Spanish explorers made the Sweet Potato known to Europe. But since sweet potatoes came from the tropics, they never caught on as an essential food crop in Europe as they did in warmer regions.

Sweet potatoes quickly claimed their place as a staple food crop for humans and livestock alike in areas where they grew successfully. Sweet potatoes will produce a good crop even on very poor soils as long as they have the mild temperatures they require. Some would consider sweet potatoes an ideal crop; they have few pests, the fast spreading vines shade out most weeds that emerge, and sweet potatoes store well after harvest.

A 1992 study by the Center for Science in the Public Interest compared the nutritional value of sweet potato to other vegetables. Sweet potatoes ranked highest, with Irish or white potatoes a very distant second.

Historically, sweet potatoes were a great find for the English colonists in what is now the Southern U.S. Not only could sweet potatoes be grown and stored easily, they also offered a great deal of nutritional value. The proliferation of sweet potatoes across the southern U.S. combined with a low point of American History fueled the confusion of the name sweet potato and yam that we still see today.

Since the sweet potato was such a staple food source in the Southern colonies, it was also commonly fed to African slaves that worked on the plantations in the South. They called the sweet potato “nyami”, from a Fulani word meaning “to eat” or from the Twi word “anyinam” referring to the true yam native to Africa and Asia. It was a matter of time before markets advertised sweet potatoes as yams—the name stuck.

What we eat on our Holiday tables is most likely the sweet potato. Although the name yam and sweet potato have been used interchangeably in stores, in recent years the USDA has attempted to regulate the use of the name. The name “sweet potato” must accompany any appearance of the word “yam” on a label.

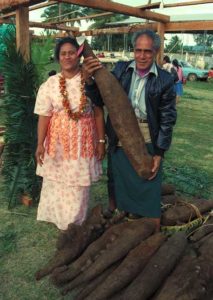

Though true yams grow underground from a vine and vaguely resemble sweet potatoes, they tend to be more cylindrical, and often have “toes” sprouting from them. They can also be a lot larger than any sweet potatoes– some grow to astounding sizes, up to seven feet long weighing 150 pounds! Tough, difficult to remove skin covers the yam’s white to bright yellow flesh.

Although many yams contain more sugar than sweet potatoes, they require special preparation before they are safe to eat. Yams contain chemicals including oxalates that can have adverse health effects if eaten raw. Typically, yams go through cycles of boiling, pounding and otherwise leaching out these harmful compounds before they are safe to eat.

Tongan farmer showing off his prized yams. Photo: James Foster

Cultures that depended on yams for food often passed down legends where yams were magic or gifts from the heavens. In Samoa, Tonga, the names of the days of the week and moon phases all referred to yams and growing them.

Yams, like other plants, have a connection to modern medicine. In 1940’s Mexico, plant biochemist Russell Marker developed a process to extract chemicals from Mexican yams and convert them into progesterone, a steroid hormone. Later, he refined his process even further and synthesized the male hormone testosterone, and the female hormone estrone.

This discovery paved the way for pharmaceutical companies to have access to inexpensive sources of steroids, which could be used to manufacture products like oral contraceptives and cortisone drugs.

You may see yams more often in the U.S., particularly in ethnic markets. Yams grow very much like sweet potatoes, but need up to a year of frost-free weather before harvest, unlike sweet potatoes which only need 100-150 days to harvest. So, unfortunately, growing true yams are best left to climates much warmer than central Illinois.

On the other hand, sweet potatoes are a great choice for home gardeners in central Illinois. Unlike white potato plants which grow from pieces of a “seed potato” containing numerous “eyes” which sprout after planting, sweet potatoes are planted as small plants. Individual plants grow from the eyes of the sweet potato called “slips”. The slips are removed from the sweet potato and typically sold in a bundle.

How to grow your own sweet potatoes

- Buy sweet potato slips or grow your own. University of Missouri has detailed instructions here. The author stresses the importance of using certified seed potatoes for starting slips, which means the potatoes are certified to be free of disease. I know some gardeners that have started their own slips for longer than I’ve been alive, and they’ve never had a problem. Use common sense here– if you use your own potatoes only use the best ones. The gardeners I know save the best potatoes each year to create slips for the following year.

- Plant the slips only after the danger of frost is past. Remember sweet potatoes are a warm weather crop and cold temperatures will damage the plants. Find your average date of last frost here. Keep in mind this link gives the date with a 50% chance that it is the last frost. 50% of the time this date is not the last frost. A handy chart of suggested planting dates based on your location can be found here.

- The best soil for sweet potatoes is very loose and may be amended with sand and compost or other organic matter. Fertilizers should contain low levels of nitrogen and high levels of phosphorus to encourage tuber formation.

- Plant slips 12 to 18 inches apart in rows 3 to 4 feet apart. Check out this University of Illinois page for more detailed information on growing and harvesting sweet potatoes. If you plan to store your sweet potatoes, pay special attention to the information on curing your sweet potatoes after harvesting.

We used to grow sweet potatoes in our garden quite successfully– until the local mice and voles discovered our garden. That year every beautiful sweet potato we dug was just a hollow shell, left behind by some fat and happy rodents.

These days I prefer to get my sweet potatoes from some community gardener friends in Decatur, IL. For some reason they all assumed I didn’t know how to cook and were surprised when I brought a sweet potato soufflé to their annual Harvest Banquet.

They raved about it that day, and the next year asked for me to bring it again– but they couldn’t remember the name. One gentleman called it “that sweet potato shuffle thing”. So from that point on this dish has been renamed “The Sweet Potato Shuffle”. I can’t help but think of the 1985-86 Chicago Bears when I make it. This year my mom is changing up the old standby of sweet potatoes with mini marshmallows in favor of “The Shuffle”.

“The Sweet Potato Shuffle” (Formerly known as Sweet Potato Soufflé)

Ingredients:

6 Cups mashed sweet potatoes

1 Cup sugar

2 eggs

1/2 Cup milk

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/4 Cup butter

1 teaspoon vanilla

1 teaspoon cinnamon

- Mix well, place into greased pan.

Topping:

1 Cup brown sugar

1/2 Cup flour

1/4 Cup butter

1 Cup pecans (whole or pieces)

- Crumble topping over potatoes. Bake at 350 degrees for 35-45 minutes uncovered. * I’ve had great luck baking this dish in the oven directly in the removable crock of a slow cooker. When it’s done baking, set the crock back in the base of the slow cooker on ‘low’ or ‘warm’ until ready to serve.

If you liked this post, please subscribe to Grounded and Growing today and receive your copy of “15 Tips to Become a '15 Minute Gardener'” so you can spend less time working ON your garden and more time enjoying being IN your garden.! It’s absolutely free. When you join the Grounded and Growing community, you’ll finally take the garden off your “To-Do” list and allow yourself time to enjoy your garden and savor the peace and serenity there. I tell subscribers about new posts as soon as I hit ‘publish’ and send weekly-ish updates on what’s going on in my garden– good, bad AND ugly.

Interesting story on how sweetpotatoes got to Polynesia: http://www.nature.com/news/dna-shows-how-the-sweet-potato-crossed-the-sea-1.12257 Apparently they made the crossing from South America way before European explorers started carrying them around and spreading them.

Thanks for sharing Margaret! That sure adds a twist to the story of sweet potatoes!