There’s something about the buttery sweet vanilla goodness of sugar cookie dough that instantly transports me to Christmas time no matter what time of year it is. I know it’s not safe to eat the dough because of the raw egg factor, but I do. And I’ve let my 3-year-old son eat it too. Please don’t send me hate mail.

Maybe you’re like me and you love to bake during the Holidays, or maybe you’re like me and you love to eat baked treats during the Holidays too. Whatever your preference is, I don’t think any of us can argue there is something about scents and flavors of spices that conjure up memories, especially this time of year. Like most of us, I never gave spices a second thought as to where they came from. But my orchid collection in grad school changed that.

Now that I’m a mom, some of my random plant information comes in handy for my 3-year-old’s seemingly nonstop litany of questions. Maybe you too have an inquisitive preschooler in your life. Or maybe you’re just a curious gardener like me. At the very least this information could give you something to talk about at your next Holiday party.

Vanilla

I knew that vanilla came from an orchid, but I had no clue what it looked like until I was given a Vanilla orchid in graduate school. A friend had taken cuttings from their much larger plant to share, and I have a hard time passing up free plants. Of course, the thought crossed my mind that I might be able to grow my own vanilla extract. But then I learned just producing Vanilla beans takes at least nine months, and is only the first step in vanilla production.

The Vanilla orchid is not as showy as you might think. Photo: Everglades National Park

Vanilla extract comes from vanilla beans, the fruit of the Vanilla orchid. Initially, Mexico and Central America produced the world’s vanilla, since it was the only place in the world that also hosted the insect that would pollinate the Mexican orchid Vanilla planifolia. Commercial production of Vanilla beans outside of Mexico and Central America became possible once someone figured out how to hand-pollinate the flowers and bypass the insect pollinator. Even though there are over 100 known Vanilla species, most of the vanilla grown commercially today is still the Mexican species Vanilla planifolia, also called “Madagascar-Bourbon” vanilla produced in Madagascar and Indonesia.

In all honesty, vanilla flavored anything has never been my first choice, even though it’s considered the most popular flavor and scent world-wide. To me, it’s always seemed too plain. Too blah. I’d rather have chocolate. No matter what my opinion though, the world appreciates vanilla, as historians estimate humans have used vanilla for at least 1,000 years.

I’ve loved baking from the moment I started helping my mom as a young girl. Even as a poor graduate student, I baked. Vanilla extract is used in many of my favorite recipes, and I commonly bought artificial vanilla extract just because it was cheaper. I rationalized that the artificial stuff was essentially the same as the real extract that cost six times as much. Boy was I wrong.

Real vanilla extract contains several hundred chemical compounds.

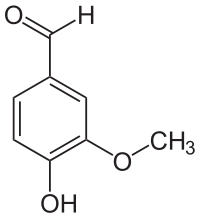

In 1858, chemist Theodore Nicolas Gobley isolated the chemical compound that dominates vanilla extract and named it vanillin. Vanilla as a flavor was in high demand, but real vanilla extract was exceedingly rare and expensive.

The primary compound found in Vanilla extract– vanillin.

Seeing a money-making opportunity, within 20 years companies developed a way to synthesize vanillin from pine bark. Over the years, other cheap and abundant materials used to create vanillin include: clove oil, wood pulp from the paper industry, and most recently petrochemicals.

Worldwide demand for vanilla flavoring still outpaces the supply of natural vanilla extract today, which is part of the reason real vanilla extract is so expensive. One company, Rhodia, is marketing Rhovanil Natural®, a “natural” vanilla flavor created by microorganisms that convert components of rice bran into vanillin. While it is technically “natural” and “non-GMO”, it’s not from the Vanilla orchid. You decide what that means to you.

Real vanilla remains relatively expensive and scarce largely because of the complicated and lengthy production process. When I first acquired my Vanilla orchid, I assumed as many of us might, that the flower and fresh Vanilla beans must smell like vanilla. In reality, they don’t smell like anything.

The distinctive scent of vanilla develops only after a complicated three-month curing process of heating and cooling the beans. The finished product is sold as is, or may be transformed into vanilla extract, which is nothing more than using ethyl alcohol to remove the vanilla flavoring from cured Vanilla beans.

Make your own “homemade” vanilla extract

- Slice vanilla beans in half lengthwise

- Insert halved vanilla beans in a bottle of your favorite ethyl alcohol (most recipes use vodka, but anything 80+ proof (80 proof = 40% alcohol) could work). Recipes I’ve seen suggest 3-4 Vanilla beans per 8 ounces of alcohol.

- Shake the bottles occasionally, and after a few weeks in a cool dark spot, you will have made your own vanilla extract.

- Leave the vanilla beans in the bottle to be extra fancy and extract every bit of flavor.

Considering the amount of labor that goes into producing Vanilla beans, it’s no wonder that vanilla is the second most expensive spice in the world after saffron. If you’re wondering what happened to my Vanilla orchid, I never did grow my own vanilla extract. I was never successful at getting the plant to flower, although it grew vigorously for several years in my apartment. I have, however, grown to appreciate the cost and flavor of real vanilla extract.

Cinnamon

This familiar spice is the inner bark of several different species of trees in the genus Cinnamomum, a tree native to South East Asia. To harvest cinnamon, a tree branch is cut from the main tree, and its woody outer bark is removed. A hammer loosens the inner bark by repeatedly striking it. The inner bark peels off in long strips cut to about three feet in length. These strips curl naturally as they dry. These curled strips called “quills” are cut into smaller pieces for sale. You may have some of these quill pieces in your pantry– most people call them a cinnamon stick.

Cinnamon has been used for thousands of years. Records dating back to 2000 B.C. indicate it was imported into ancient Egypt. Cinnamon was a highly prized spice in the ancient world. It was commonly offered to God in religious ceremonies, and only the richest citizens would have been able to afford to use cinnamon in their daily life. The source of cinnamon was a mystery to most of the world until at least the Middle Ages; spices like cinnamon were very valuable, so those who were able to obtain these spices typically guarded their sources fiercely.

The flavor of cinnamon varies depending on the species of Cinnamomum it is obtained from. The cinnamon typically used in cooking is produced from grinding the cinnamon quills, or sticks into powder. Most types of cinnamon can be ground easily in a coffee or spice grinder at home, but some are so thick and coarse they will damage home grinders.

The smell of cinnamon is second only to vanilla in my mind as the scent of Christmas time. To keep the sweet smell of the Holidays around a little longer, try making cinnamon ornaments. If you still need more cinnamon in your life, do a search for “cinnamon crafts” online. I smell a future post!

Nutmeg

The genus Myristica, an evergreen tree native to Indonesia produces the seed that when ground we recognize as nutmeg.

Nutmeg trees must be at least seven to nine years old before they will produce seeds, and typically don’t reach their full potential for seed production until they are at least 20 years old. These trees are dioecious, meaning there are male and female plants. Only the females produce seed. It takes six to eight years of growth before it will flower, revealing whether it is male or female.

Nutmeg fruit containing nutmeg (brown) covered with mace (bright red). Photo: slashme

The nutmeg tree produces a small fruit that resembles a green peach. Some cultures use this fruit to make jam, or thinly slice it and cook it with sugar to make a crystallized candy. The seed of this fruit, which is about the size of a large acorn, is what is ground to make nutmeg. Each seed is covered with a lacy, bright red membrane that when dried is the spice known as mace. Mace has a flavor similar to nutmeg but is described as more delicate.

Historically nutmeg has been used for thousands of years, and was highly valued because of the dangerous travel involved in obtaining most spices from faraway lands. In Elizabethan times it was believed that nutmeg would ward off the plague.

Allspice

Allspice is the dried unripe fruit of Pimenta dioica, a medium sized tree native to Mexico and Central America. The English gave it the name “allspice” in the 1600’s, thinking it tasted like cinnamon, nutmeg and cloves. It’s no surprise then, that if you run out of allspice in the middle of cooking, many sources suggest this allspice substitute: mix equal amounts of cinnamon, nutmeg and cloves.

Another name for allspice is Jamaica pepper. It is historically an important spice in Caribbean cooking. The leaves of the allspice trees are also used in cooking, much like how a bay leaf is used. Christopher Columbus introduced allspice to Europe following his second voyage to the new world.

Cloves

The familiar scent of cloves comes from the dried flower buds of the evergreen tree Syzygium aromaticum, native to Indonesia. The name clove is derived from the Latin ’clavus’, meaning nail, which the clove vaguely resembles.

Cloves were another spice highly prized by Europeans. Historians report that during the 17th and 18th centuries, cloves were worth their weight in gold in England.

Historically cloves have been used for a wide range of medical applications. Modern science has shown the most abundant compound in cloves is eugenol, which is responsible for its distinct aroma. This chemical has demonstrated anesthetic and antiseptic properties.

These orange pomanders are 5 years old and still smell good! Click on the link for printable instructions to make your own.

My favorite thing to do with cloves besides baking is making a Clove Orange Pomander. I have some at home that are five years old and are still in good shape. If you have oranges left over after making pomanders, use them to make this festive Dried Orange Garland. It will last for years as long as you keep it dry.

Though the scents and flavors of these spices instantly make us think of being home for the Holidays, they actually come to us from all corners of the world. We take for granted the modern availability of these spices, but historically they were often hard to obtain and beyond the budget of all but the most wealthy. But today most of us will enjoy these spices and more in our Holiday celebrations.

If you liked this post, please subscribe to Grounded and Growing today and receive your copy of “15 Tips to Become a '15 Minute Gardener'” so you can spend less time working ON your garden and more time enjoying being IN your garden.! It’s absolutely free. When you join the Grounded and Growing community, you’ll finally take the garden off your “To-Do” list and allow yourself time to enjoy your garden and savor the peace and serenity there. I tell subscribers about new posts as soon as I hit ‘publish’ and send weekly-ish updates on what’s going on in my garden– good, bad AND ugly.

Leave a Reply